"Hollywood's Golden Age (of Queer Coding)" Transcript

A video essay — I mean, a reading of Vito Russo's book — covering the fifties, Ben-Hur, Rope, and skipping over nearly all of the Lesbian and Trans examples.

The Queer History of Hollywood (Thumbnail)

Queen Christina

Ben-Hur

Laurel and Hardy

Rope / Rope's End

You can view the archive of this video on the Internet Archive or on the Internet Archive

Auto-transcribed by YouTube, downloaded by TerraJRiley.

Formatted by Tustin2121.

Thanks to LVence for tracking down and highlighting various sources.

- Rυѕsο, V. (1987). Tһе Celluloіԁ Closet: Hoⅿoseхuаlitу iո the Moνies (Revised ed.) Quality Paρerbaсk Book Club, Neѡ York. HarperCollins née Harper & Row. https://archive.org/details/celluloidcloseth00russ/page/n9/mode/2up

- James continues a 'direct quote' that doesn't exist. (Jump to )

- James, basically reading beat for beat from Russo's book, skips over any discussion about Lesbian or Transgender films of the era that Russo goes into. (Jump to )

Video transcript is on the left. Plagiarized text is highlighted, as is misinformation. For more info, see how to read this site

Fact-checking commentary or found plagiarized content is on the right for comparison Plagiarized text is highlighted.

[sponsor plug]

The second in a series of eight videos looking back at the queer history of Hollywood from the beginning of the film industry to modern blockbusters and streaming.

PATREON LINK: [link]

James's Twitter: [link]

Nicks Twitter: [link]

00:00 Introduction

03:04 Chapter 1

12:05 Chapter 2

18:49 Chapter 3

#Documentary #lgbt #movies

This video is brought to you by Manscaped.

In Hollywood's early years, homosexuality found its way on screen in ways both secret and obvious to the filmmakers behind the camera. Audiences rarely pushed back against these depictions, but those who did were loud, if not legion. Women's suffrage groups and the Catholic Church were the most dedicated to removing gay and lesbian content from Hollywood movies.

And with the institution of the Motion Picture Production Code, they more or less succeeded. Filmmakers could now be fined or blacklisted for including gay and lesbian characters in their movies, and some films such as Dracula's Daughter were heavily edited to remove any overt lesbian content. But, go figure, a bunch of people who came up in the industry through artistic roots knew how to manipulate literary devices in visual language to still include gay themes and characters in their movies. Though in much less obvious ways.

Along with World War II and a coming end to what was referred to as the Golden Age of Hollywood, a time of gay invisibility had swept over the industry. But it was an invisibility that you could see through, if you knew how to look.

But before we explore the queer coding of the aging days of the golden age of Hollywood, first a word from our sponsor.

[Sponsor read]

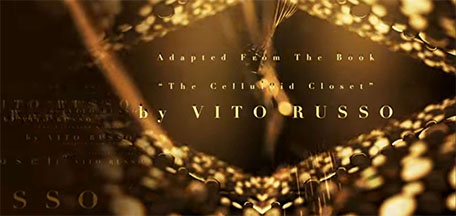

Telos Pictures

presents

Written by

James Somerton

Adapted From The Book

"The Celluloid Closet"

by VITO RUSSO

Executive Producers

[Five Patron Names]

Executive Producers

[Five Patron Names]

Executive Producers

[Five Patron Names]

UNREQUITED

The History of Queer Hollywood

[Over black]:

Episode Two

The Invisible Men

Even though Hollywood didn't always tell the truth, this kept a lot of unwelcome facts and small problems from getting in the way of the American Dream. Even though gay and lesbian people were often the ones who made these dreams come true, they were never a part of it.

It is said that Sam Goldwin, founder of Goldwyn Pictures, which was one of the three studios that merged to create MGM, once wanted to film The Well of Loneliness by Radcliffe Hall. But when a producer told him they couldn't because the main character was a lesbian, Goldwyn simply responded by saying:

"So what? We'll make her American!"

Hollywood's admittedly casual relationship with the truth protected the American dream from a host of unwanted realities and niggling intrusions. And while lesbians and gay men were often among the architects of that dream, they were never a part of it. It is said that Samuel Goldwyn once suggested filming Radclyffe Hall's notorious The Well of Loneliness, only to be informed by a producer that he could not because the leading character was a lesbian. "So what?" Goldwyn retorted. "We'll make her an American." Apocryphal or not, the simplicity of his solution captured the spirit of the truth. It was not as American as apple pie to be queer, and the closeted visions of countless gay screenwriters, directors, actors and technicians were submerged into the heterosexual, all-American fantasies of the majority. Gay characters and references to the existence of homosexuality were routinely laundered off the screen for the better part of half a century.

Despite Goldwyn's confusing lesbian for Lebanese, the Americanization of lesbianism did happen, and meant nothing more than the simple refusal to deal with it honestly. It was an imitation of the American fear of sexuality in general and the American duplicity regarding sexual deviance in particular.

In all actuality, it was the same invisibility that gays experienced in real life, only replicated in the movies. Despite this gays continued to make an appearance as subtextual phantoms that represented the fear of homosexuality itself. They served as his alien life forms that were yet firmly established as part of the culture in every walk of life. And they formed the shadowy counterpart to the concept of the American dream.

Sissies and tomboys were used as yardsticks for what was deemed acceptable behavior in a culture that was so preoccupied with the upkeep of sex norms and the celebration of everything masculine.

And so the Americanization of lesbianism meant simply an unwillingness to deal with it openly, an aping of the American cowardice about sex in general and the American hypocrisy about sexual deviation in particular. Technically. homosexuals were just as invisible onscreen as they were in real life. They continued to emerge, however, as subtextual phantoms representing the very fear of homosexuality. Serving as alien creatures who were nonetheless firmly established as part of the culture in every walk of life, they became the darker side of the American dream. In a society so obsessed with the maintenance of sex roles and the glorification of all things male, sissies and tomboys served as yardsticks for what was considered normal behavior. The discomfort that has consistently arisen in response to "buddy" films springs from the paranoia and fear that surrounds exclusively male relationships. American society has always begun at square one, with the belief that men are never attracted to each other as masculine equals (one of them is always seen as wanting to be a woman or to act like one). Thus the denial of the existence of homosexuality did not suppress the national fear of it but instead served to point it up continually. Nor did this denial belie for long the fact of it in history.

One performer who happily ignored these sex Norms was Greta Garbo, whose performance as Queen Christina in the film of the same name released in 1934, was a challenge to the standards of sexual and gender behavior that were considered acceptable at the time. It was the collision on screen of her own androgynous aesthetic, with the reality of Christina's affinity for masculine clothes and activities, that gave the picture a realism that was uniquely its own.

Garbo — who would express her desire to be in a film version of Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray, with herself in the title role and Marilyn Monroe as a young girl ruined by Dorian — created a particular dynamic in Queen Christina, one that penetrated the queer erasure of the script. Her forlorn longings to escape her gloomy destiny of marriage and her skillful rejection of a series of male suitors are broken in the first part of the film by her encounter with the Countess Ebba Sparre, played by a Elizabeth Young.

Their brief scene together is charged with sexuality and real affection. In that scene, Garbo lifts the emotional barriers to characterize her encounters with mail suitors. Ebba suggests brightly that they go for a sleigh ride, but Christina tells her sadly:

The movie was released late 1933.

In 1933, less than a year before the release of Queen Christina, Rouben Mamoulian's romantic fantasy starring Greta Garbo as the Swedish monarch, Elizabeth Goldsmith published Christina of Sweden ("A Psychological Biography"). In reviewing the book and anticipating the film by Mamoulian, Lewis Gannett wrote in the New York Herald Tribune, "The one persistent love of Christina's life was for the Countess Ebba Sparre, a beautiful Swedish noble. woman who lost most of her interest in Christina when Christina ceased to rule Sweden . . . the evidence is overwhelming, but will Miss Garbo play such a Christina?"

Garbo did no such thing, of course, but the collision onscreen of her own androgynous sensibility with the fact of Christina's love for male attire and pursuits gave the film a truth of its own. Garbo, who once expressed to Katharine Comell her desire to play in a film version of Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray with herself in the title role and Marilyn Monroe as a young girl ruined by Dorian, created a particular dynamic in Queen Christina, one which penetrated the fundamental deceptions of the script. Her melancholy longings to escape her destiny (marriage) and her deft rejections of a series of male suitors are interrupted in the first half of the film by her encounter with the Countess Ebba. Sparre (Elizabeth Young). Their brief scene together is charged with sexuality and real affection, the only such display in the film between Garbo and another woman. In that scene Garbo lifts the emotional barriers that characterize her encounters with male suitors. When Ebba bursts into the queen's chamber, the two kiss passionately on the lips. Ebba suggests brightly that they go for a sleighride, but Christina tells her sadly that Parliament awaits and that they will see each other that evening. "Oh, no we won't!" Ebba pouts. "You'll be surrounded by musty old men and musty old papers, and I won't be able to get near you." The Queen caresses her face gently and promises that they will soon go away to the country together "for two whole days."

Christina: "I can't now."

Abba: "Oh why not?"

Christina: "Ambassadors, treaties, councils..."

Abba: "How boring!"

Later, when pressed by a statesman to marry and produce an heir to the throne, Christina refuses.

Later, when pressed by a statesman to marry and produce an heir to the throne, Christina defiantly refuses. "But, your majesty." he cries, "you cannot die an old maid!" Dressed now in men's riding clothes, she pauses at the door and replies, "I have no intention to, Chancellor. I shall die a bachelor!" and she stomps out of the room. The battle between the heroic tomboy and the tortured, doomed queen is sustained throughout the film, and her love affair with Antonio (John Gilbert) does not resolve it. Her need to escape the role assigned her by life was Christina's true driving passion; Queen Christina makes this abundantly clear.

Chancellor: "But your majesty! You cannot die an Old Maid!"

Christina: (stops, spins) "I have no intention to, Chancellor. I shall die a bachelor!" (turns and leaves)

Her need to escape the role assigned her by life was Christina's true driving passion. Queen Christina makes this abundantly clear.

She flees into the snow later in the film when she discovers that Ebba Sparre has betrayed her love. That is when she meets Antonio, the one man who seems to accept her and love her for all the things that so horrify her court. But he falls in love with her, thinking at first that she's a man. And he seems quite willing to explore whatever this strange situation may bring.

Gazing out the window, Christina murmurs, "The snow is like a wild sea, One could go out and be lost on it." She flees into the snow a little later, when she discovers that Ebba Sparre has betrayed her love. That is when she meets Antonio, the one man who seems to accept her and love her for all the things that so horrify her court. He falls in love with her, thinking at first that she is a man, and he seems quite willing to explore whatever this strange situation may bring. In an amusing scene, Antonio's servant enters the bedroom at the inn where Christina and Antonio have spent the night, to find that his master is still in bed with the young "man" with whom he had retired the night before. He takes an order for two morning chocolates and withdraws in astonishment.

In the early days of Hollywood, Queen Christina stood out due to the fact that it included a character that was unmistakably bisexual. As well as many instances of bisexuality in the narrative of the film itself.

At the time, the lives of notable gay men and lesbians were either portrayed in a manner that was drastically different from their actual experiences, or were not addressed at all in biographical films. This straight-washing of history has only marginally changed in modern cinema, as seen by the fact that films such as Troy, A Beautiful Mind, and The Imitation Game more or less ignore or completely erase the fact that its primary characters are gay or bisexual.

It's one of the reasons why audience members were taken aback by the lesbian relationships that were depicted in The Favorite. Even in the late 2010s, audiences of historical biopics anticipated that queerness would be erased from historical recreations.

Accidents such as the collision of Garbo's chemistry and Christina's stubborn maleness, the kind that produce something more than is in the script, happen rarely, though not as a rule in biographies; the lives of famous lesbians and gay men were altered significantly or were not attempted. The need for invisibility is reflected in the very character of the American experience: heroes may certainly not be homosexual. Real-life gays almost never tampered with the illusions; rather, they subscribed to them. In 1946, Cole Porter and Monty Woolley, lifelong friends but not lovers, created their own dismal myth in Warner Brothers' Technicolor musical "biography" of Porter, Night and Day. Porter and his wife Linda, by choosing Cary Grant and Alexis Smith for the title roles, opted for a sophisticated Ozzie and Harriet look while Monty Woolley, playing himself, chose the grand old man of letters motif- pinching the chorus girls and all the rest of the heterosexual repertoire.

The portrayal of noted persons as heterosexual, without regard for their true to life sexuality, has never been seen as a serious offense against a person's identity until recently. Not even by the person whose life is falsified. No, it was better to be straight. Even queer audiences themselves believe that, especially in Hollywood's Golden Age, when it was a dirty secret most people yearned to be rid of.

The portrayals of noted persons as heterosexual without regard for their true sexuality has never been seen as a serious offense against a person's identity not even by the person whose life is falsified. No, it is better to be straight. And gays believed that. Films such as The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965) and Khartoum (1966) reflected the care with which their sources masked or denied the homosexuality of Michelangelo and General Charles Gordon, just as uninspired confections of the Fifties such as Valentino (1951), Hans Christian Andersen (1952) and Alexander the Great (1956) bypassed history for the safe illusions held tightly by the majority.

But there was an odd dichotomy developing in Hollywood, whereas lesbian or bisexual female characters could be redeemed in a film by being paired off with the right man in the end, bisexual or gay male characters had no such luxury. In the film Adam's Rib, which was released in 1949, David Wayne plays the role of Kip, who is a yardstick sissy par excellence.

Kip serves as Katherine Hepburn's... girlfriend. Acting as a high-class Ethel Mertz to her feminist Lucy Ricardo. Despite Catherine Hepburn's defense, Spencer Tracy's apparent unease around him cannot be denied. As they were leaving the room following a heated discussion over feminism, Wayne said to Hepburn:

Open contempt for men who are perceived to be like women was not new. In John Ford's Three Bad Men (1926), the grizzly "Bull" (J. Farrell MacDonald) tells a fancy Dan who says he has just reached manhood, "Then you'd better reach again." Essentially the same scene occurs in the "feminist" Adam's Rib (1949), in which David Wayne's Kip, a yardstick sissy par excellence, functions as Katharine Hepbum's girlfriend, a high-class Ethel Mertz to her feminist Lucy Ricardo. Spencer Tracy is clearly uncomfortable with him in spite of Hepbum's defense ("Oh, darling. He's so sweet"). Leaving the room after a heated feminist debate, Wayne says to Hepbum, "Amanda, you've convinced me. I might even go out and become a woman!" When Wayne has gone, Spencer Tracy mutters to Hepbum, "Yeah, and he wouldn't have far to go, either." Hepburn's Amanda can only whisper, "Shhh! He'll hear you," an indication that her feminism, like that of contemporary feminists who want their sons to grow up to be "real men," goes only so far and breaks down at the thought of actually obscuring sex roles altogether.

Wayne: "You've got me so convinced, I may even go out and become a woman."

[clip continues]

When Wayne has gone, Spencer Tracy mutters...

[clip continues]

Spencer Tracy: "And he wouldn't have far to go either."

Hepburn: (shushes him)

Hepburn's Amanda can only shush him, an indication that her feminism, like that of contemporary feminists who wanted their sons to grow up to be real men, goes only so far and breaks down at the thought of actually obscuring sex and gender roles altogether.

Yet the unyielding conviction in the masculine role, along with the hatred that this ideology bred, was about to be shaken to its very foundation.

The rigid belief in the male role and the intolerance that belief engendered was almost always played on a comic level and seldom emerged in the kind of dead serious hostility shown by the crowd on the bus in Up in Arms, who were reacting to the possibility of real homosexuality between two sailors. More often [...]

The buddy system that had been used during the second world war had brought troops closer together than they had ever been before. Men who loved each other's company, but always selected women to display their manhood, were forced to confront their innate sexuality in the all-male atmosphere of military forces. This brought to the surface a misunderstanding regarding men's fundamental sexuality. The worry that these heterosexual relationships between men, may in any way be interpreted as being gay, was a very genuine one.

Yet there was real danger here. War had brought men together in the buddy system, closer than they had ever been before. The all-male environment of the armed services forced to the surface a confusion about the inherent sexuality between men who preferred each other's company but always chose women to prove their masculinity. The fear that these chaste male relationships might in any way be labeled odd or queer was very real, and the movies assured that no hint of perversion would be introduced into such bonding.

And the movies made sure that there was no indication of homosexuality involved in depictions of such partnerships. There might have been less suspicion of homosexuality had the level of paranoia surrounding its very mention not been so high.

In 1946, Richard Brooks's novel The Brick Foxhole dealt with obsessive masculinity in the military. In it, a gay decorator is murdered by a soldier he brings home to his apartment for a drink. The 1947 film adaptation Crossfire made the victim a Jewish person. And thus became an example of Hollywood's maturity in dealing with anti-Semitism. The New York Times noted the change in a review but said only that the motivation for the murder had been changed "to good advantage". The novel's crucial discussion of men striking out at what they fear in themselves was omitted.

There might have been even less suspicion of homosexuality had the level of paranoia surrounding its mention not been so very high. In 1946, Richard Brooks' novel The Brick Faxhole dealt with obsessive masculinity in the military. In It, a homosexual decorator is murdered by a soldier he brings home to his apartment for a drink. Edward Dmytryk's film adaptation, Crossfire (1947), made the victim a Jew and thus became an example of Hollywood's maturity in dealing with antisemitism. The New York Times noted the change in a review but said only that the motivation for the murder had been changed from that in the novel, "to good advantage." The novel's crucial discussion of men's striking out at what they fear in themselves was omitted. It has yet to be raised onscreen with any real awareness of the magnitude of the problem.

Whenever all-male circumstances were the topic of the movies, whether they were cowboys, sports, or soldiers, the fantasy of the unfettered perennially youthful man in pure and unsullied brotherhood battled over the ever-present societal taboo against male closeness.

Whenever all-male situations were the subject of the movies, whether they involved cowboys, athletes or soldiers, the dream of the free, perpetually adolescent male in pure and unsullied comradeship fought with the ever present cultural taboo against male intimacy. Peter Pan, after all, was a fairy tale; grown men had real responsibilities that necessarily included growing up and settling down to marriage with a woman. Yet the opening title of Herbert Brenon's Beau Geste (1926) spoke of the dream.

Love of man for woman waxes and wanes.

Love of brother for brother

is as steadfast as the stars.

Now if only people wouldn't assume that all those loving brothers were as queer as three-dollar bills, men could hug without having nightmares.

Director Clarence Brown toyed with this in his film Flesh And The Devil, in which John Gilbert and Lars Hansen play lifelong friends who separate when one of them marries the woman they both love, played by Greta Garbo. By the end of the film, Garbo has slept with both of them, precipitating a reluctant duel between the two men. Trying to stop them, she falls through some thin ice and drowns. At this the men throw down their guns, embrace, and walk off into the sunset together, their arms around each other. Their bond rejoined following the intrusion of a woman.

Clarence Brown spoke of the situation in an interview:

"You can see my problem!

How to have these two leading men wind up in each other's arms and not make them look like a couple of fairies?"

Director Clarence Brown spotted the rub. In his Flesh and the Devil (1927), John Gilbert and Lars Hanson play lifelong buddies who separate when one of them marries the woman they both love (Greta Garbo). By the end of the film, Garbo has slept with her husband's friend, precipitating a reluctant duel between the two men. Trying to stop them, she falls through the ice and drowns. At this the men throw down their guns, embrace and walk off into the sunset together, their arms around each other, their bond rejoined following the intrusion of a woman.

Clarence Brown spoke of the situation in an interview. "You can see my problem. How to have the two leading men wind up in each other's arms and not make them look like a couple of fairies?" It was a tough question. The primary buddy relationships in films are those between men who despise homosexuality yet find that their truest and most noble feelings are for each other. There is a misogyny here that [...]

Joan Mellon, in her study of masculinity in the movies Big Bad Wolves, says that the less violent men were in their film personas, the more likely they were to be interested in heterosexual love. Just the opposite has been true for homoeroticism.

The perception of homosexual feelings as a brutal furtive, dangerous, force flourished in films about male bonding and violence, playing off of the idea of homosexuality being innately criminal. Gentlemen in the movies Jimmy Stewart in any movie about Small Town USA, would never even subtextually approach such relationships or feelings. The concept of the gentleman who chooses to love other men did not exist in American Film except in comedy.

Joan Mellon, in her study of masculinity in the movies, Big Bad Wolves, says that the less violent men were in their film personas, the more likely they were to be interested in heterosexual love. Just the opposite has been true for homoeroticism. The perception of homosexual feelings as a brutal, furtive and dangerous force saw it flourish in films of male bonding and violence. Gentle men in the movies Jimmy Stewart in any "Smalltown, U.S.A." picture or Spencer Tracy in Father of the Bride, for example would never, even subtextually, approach such relationships or feelings. The concept of the gentle man who chooses to love other men does not exist in American film except as slapstick comedy. Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy had the perfect sissy-buddy relationship throughout their long career, and it is naive now, looking at their films, to assume that they were not aware of and did not consciously use this aspect of their screen relationship to enrich their comedy.

In the films of Laurel and Hardy, their relationship was given a sweet and very real, loving dimension. A classic example of this, one with unmistakably gay overtones, is 1932's Their First Mistake. Hardy's wife complains that he sees too much of Laurel and not enough of her. And the two friends discussed the situation:

In the films of Laurel and Hardy, their relationship was given a sweet and very real loving dimension. The two often wound up in bed together, and their wives were almost always portrayed as obstacles to their friendship. In a classic example of this, one with unmistakably gay overtones, they play a married couple complete with newbom baby in Their First Mistake (1932), a Hal Roach film directed by George Marshall. Ollie's wife (Mae Busch) complains that he sees too much of Stan and not enough of her, and the two friends discuss the situation.

Stan: Well, what's the matter with her, anyway?

Ollie: Oh, I don't know. She says I think more of you than I do of her.

Stan: Well, you do, don't you?

Ollie: We won't go into that.

Stan: You know what the trouble is?

Ollie: What?

Stan: You need a baby in your house.

Ollie: Well, what's that got to do with it?

Stan: Well, if you had a baby . . . it would keep your wife's mind occupied. you could go out nights with me . . . and she'd never think anything about it.

So they go out and adopt a baby. When they return home with it, they discover that Ollie's wife is suing him for divorce for "alienation of affections." having named Stan Laurel as "the other woman." The remainder of the film is a beautifully timed and performed domestic scene, with Stan and Ollie in bed and the baby between them. The scene climaxes when Stan reaches into his pajama top- as if reaching for a breast to feed the baby and comes up with the baby's bottle, which he has been keeping warm.

Laurel: "But what's the matter with her anyway?"

Hardy: "Oh, I don't know. She says that I think more of you than I do of her."

Laurel: "Well, you do, don't ya?"

Hardy: "Well, we won't go into that."

Laurel: "You know what the whole trouble is?"

Hardy: "What?"

Laurel: "What you need is a baby in your house."

Hardy: "Well what's that got to do with it?"

Laurel: "Well, if you've if you had a baby and... it would keep your wife's mind occupied... and you could go out nights with me and she'd never think anything about it."

So they go out and adopt a baby. When they return home with it, they discover that Hardy's wife is suing him for divorce for alienation of affections, having named Laurel as the other woman. The remainder of the film is a beautifully timed and performed domestic scene with Laurel and Hardy in bed with the baby between them.

The obviousness of the coding has been lambasted ever since the film's release, with Charles Barr in his study of Laurel and Hardy saying that:

"There is something rather absurd about discussing this seriously at all. In the often infantile, pre-sexual nursery world in which Stan and Ollie lived, such behavior would be natural."

All this is charming, sometimes very funny and certainly of no great consequence. Yet when one suggests that there may be clues to homosexual behavior in the ways that Laurel and Hardy related to one another, it is as though one were attacking America itself. Charles Barr, in his study Laurel and Hardy, says that "there is something rather absurd about discussing this [the homosexual nature of Their First Mistake] seriously at all." In the often infantile, "presexual" nursery world in which Stan and Ollie lived, Barr argues, such behavior would be "natural."

James continues the "direct quote" even though the actual quote from Barr is done.

I'd agree that it is in fact natural, but the idea of there ever having been a "pre-sexual time" is reaching. But notice that it is the "naturalness" of Laurel and Hardy's behavior that Barr and other critics choose to defend, not the sexuality. And so it is, indeed, an attack on Americanism itself to suggest that homosexuality is present in the Laurel and Hardy routines.

In pointing these things out, one attacks the "American illusion", the illusion that there is in fact such a thing as a "real man" and that to become one is as easy as changing one's name from Marion Morrison to John Wayne. The fact is that comedy has been able to comment on sexual roles more readily than drama could, only because people may dismiss it as an impossible farce.

It is fast becoming evident, however, that there is no such thing as a "presexual" age. Notice, too, that it is the "naturalness" of Laurel and Hardy's behavior that Barr and other critics choose to defend, not the sexuality. The homosexuality is unmistakably there; it remains only for people to say that in this case such behavior would be natural to fend off charges of unnaturalness in beloved film figures. And so it is indeed an attack on America itself to suggest that homosexuality is present in the Laurel and Hardy routines. In pointing these things out, one attacks the American illusion—the illusion that there is in fact such a thing as a real man and that to become one is as easy as changing one's name from Marion Morrison to John Wayne. The fact is that comedy has been able to comment on sexual roles more readily than drama could do only because people may dismiss it as impossible farce.

Neglected sissy-buddy relationships exist even in classic cartoons. Walt Disney may not have liked hearing it, but there are gay overtones in the relationships of more than one pair of beloved animated figures from his classic years. In 1940's Pinocchio, Honest John and Gideon, a fox and a cat, are best friends who procure lost boys for sale to an evil coachman who takes them to Pleasure Island. They seduce Pinocchio with the hit song High Diddly D, the second line of which is "high diddly day, an actor's life is gay".

Neglected sissy-buddy relationships exist even in classic cartoons, and a look at Saturday morning television will discover a preponderance of sissy-bully plotlines. Walt Disney may not have liked hearing it, but there are gay overtones in the relationships of more than one pair of beloved animated figures of the classic years. In Pinocchio (1940), Honest John and Gideon, a fox and a cat, are best friends who procure lost boys for sale to an evil coachman who takes them to Pleasure Island. They seduce Pinocchio with the hit song "Heigh Diddley Dee" (the second line of which is "Heigh diddley day, an actor's life is gay"), and away he goes—twice.

In Cinderella, everyone's favorite mice Jaq and Gus Gus, volunteer to help finish Cinderella's dress in time for the ball. But they are quickly admonished by a female mouse to "leave the sowing to the women". Their relationship grows throughout the film, and later when Cinderella describes how she was swept off her feet by the handsome prince, Gus Gus puts an arm around Jaq's shoulder and holds him close.

And of course, from the competition, there was Bugs Bunny, giddy to throw on a dress and a wig at the first available opportunity.

In Cinderella (1950), everyone's favorite mice, Jock and Gus-Gus, volunteer to help finish Cinderella's dress in time for the ball. But they are quickly admonished by a female mouse to "leave the sewing to the women" and told to go find "some trimmin'" for the dress. Their relationship grows through their friendship in dangerous times, and later, when Cinderella describes how she was swept off her feet by the handsome prince, Gus-Gus, sighing evenly, puts an arm around Jock's shoulder and holds him close. After a minute, Jock realizes that they are sitting on a log at the side of the road in each other's arms, and homosexual panic seems to set in on the little fellow. Pulling away quickly, he gives Gus-Gus a quizzical look of wary scrutiny, as if to say, "Hmmm, there's something funny about this mouse." And there was. Just a few years after Cinderella, Tom Lee, a shy and sensitive student in Tea and Sympathy, would be told much more forcefully to "leave the sewing to the women." Everyone looked at Tom Lee sort of funny—and scratched their heads, too, just like Jock the mouse.

The body text of Celluloid Closet does not mention Bugs Bunny. However, an image of Bugs Bunny is at the bottom of page 75, with the caption "Bugs Bunny encounters a fey Oscar in Stick Hare."

The real emotions in the movies at the time with exceptions for films like Gone With the Wind always took place between men. Men had been the important forces at work, both as instigators of all the action and plots and as instigators of the films themselves, by deciding what movies should and should not be made.

Again, these interpretations arise invariably from the fear of homosexuality, seldom from the fact of it. The expendability of women in buddy films was one reason for that fear. Heterosexual romance was often just a standard plot ingredient, thrown in at regular intervals because it had to be there, and lacking the emotional commitment that the filmmaker failed to give it. The real emotions in the movies, as well as in the movie industry, have always taken place between men. Men have been the important forces at work, both as instigators of all the action in the pictures and as instigators of the films themselves, by deciding what movies should be made and how. Subtexts presented themselves constantly but were left unresolved, just as the women waited around while the boys recreated their adolescent fantasies, unencumbered by an emotional commitment to anything but each other and a good time.

When screenwriter Gore Vidal discussed the script for the 1959 version of Ben-Hur with director William Weiler, they concluded that the rivalry between Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) and his boyfriend Masala (Stephen Boyd) was insufficiently motivated by a single political scene in which Ben-Hur refuses to Aid the Roman cause, despite his friend's pleas.

Vidal described the problem:

"I proposed the notion that the two had been adolescent lovers and now Masala has returned from Rome wanting to revive the love affair but Ben-Hur is not. He has read Leviticus and knows an abomination when he sees one.

I told Wyler...'This is what's going on underneath the scene — they seem to be talking about politics, but Masala is really trying to rekindle a love affair,' and Wyler was startled. We discussed the matter, and then he sighed, "Well. Anything is better than what we've got in the way of motivation, but don't tell Chuck.'

I did tell Stephen Boyd, who was fascinated. He agreed to play the frustrated lover. Study his face in the reaction shots in that scene, and you will see that he plays it like a man starving."

When screenwriter Gore Vidal discussed the script for Ben-Hur (1959) with director William Wyler, they concluded that the rivalry between Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) and his boyhood friend Messala (Stephen Boyd) was insufficiently motivated by a single political scene in which Ben-Hur refuses to aid the Roman cause despite his friend's pleas. Vidal describes the problem.

I proposed the notion that the two had been adolescent lovers and now Messala has returned from Rome wanting to revive the love affair but Ben-Hur does not. He has read Leviticus and knows an abomination when he sees one. I told Wyler, "This is what's going on underneath the scene-they seem to be talking about politics, but Messala is really trying to rekindle a love affair," and Wyler was startled. We discussed the matter, and then he sighed, "Well. Anything is better than what we've got in the way of motivation, but don't tell Chuck." I did tell Stephen Boud, who was fascinated. He agreed to play the frustrated lover. Study his face in the reaction shots in that scene, and you will see that he plays it like a man starving.

It was 1959, and filmmakers were on the verge of new creative freedoms. Vidal was saying that it made sense that the two men should be attracted to each other. Theirs was the most vibrant and interesting relationship in the film. Wyler later told Vidal:

"The biggest mistake we made was the (straight) love story. If we had cut out the girl all together and concentrated on the two guys, everything would have gone better."

Director Howard Hawks always concentrated on men in his films. And in his films, things went better. [Chuckles] Better than in Ben-Hur. at least.

It was 1959, and the screen was on the verge of a new freedom. Vidal was saying that it made sense that the two men should be attracted to each other. Theirs was the most vibrant and interesting relationship in the film. Wyler later told Vidal, "The biggest mistake we made was the love story. If we had cut out that girl [Haya Harareet] altogether and concentrated on the two guys, everything would have gone better." Howard Hawks always concentrated on the guys, and in his films things went better- better than in Ben-Hur, at least. Dealing almost always with close, dependent, emotional male relationships, his films were informed with a particularly schizophrenic sensibility with regard to maleness and the intrusion of women into its world. His early feature Fig Leaves (1926) is typical of the kind of male celebration that saw women as mothers or mattresses and took great care to deny any feminine implication in the closeness of comrades.

In 1948's Red River, Hawks' only use for Joanne Dru was to have her tell John Wayne and Montgomery Clift what we can already see:

In Red River (1948), Hawks' only use for Joanne Dru is to have her tell John Wayne and Montgomery Clift what we can already see. "Stop fighting!" she screams in the climactic scene. "You two know you love each other." Yet the nature of that love, despite the Clift screen persona's doing for the young Matthew what Garbo's did for Queen Christina, remained hidden. Probably the most homoerotic sequence in a Hawks film is the musical number "Is There Anyone Here for Love?" that Jane Russell performs in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953). Russell is surrounded by muscular men in briefs who seem to be oblivious to her charms ("Doesn't anyone wanna play?") but are very interested in showing off their bodies to the choreography of Jack Cole.

Andrew: "What a fool I've been. Expected trouble for days when..." (sniff) "when anybody would half a mind would know you two love each other."

Yet the nature of that love, despite Cliff's scene persona doing for his character what Garbo did for Queen Christina, remained hidden. Despite one of the most re-watched, and arguably most homoerotic scenes in any film at the time, being one in which Montgomery Clift and John Ireland compare their... pistols.

The only open acknowledgment of the homosexuality in buddy films came from those critics who attributed the misogynist attitudes of such films to the covert gayness in them. When Joseph McBride and Gerald Perry, in an interview in Film Comment, questioned Hawks about the gay undertones of his films, Red River in particular, Hawks told them it was a goddamn silly statement to make.

The only acknowledgment of the homosexuality in buddy films has come from those critics who attribute the misogynist attitudes of such films to the covert gayness in them. When Joseph McBride and Gerald Peary, in an interview in Film Comment, questioned Hawks about "gay undertones" in his films, Red River in particular, Hawks told them it was " goddam silly statement to make." And although Glenn Ford remarked in an interview that he and George Macready "knew we were supposed to be playing homosexuals" in Gilda (1946), director Charles Vidor laughed, "Really? I didn't know those boys were supposed to be that way!"

It's easy to see how directors might be... oblivious to the subtexts that are present in their own work, since homosexuality as a viable alternative has been repressed both in the lives of men and in their work. On screen, the taboo against male closeness is taken far more seriously than it is in real life, where it is more likely to be seen as a "neutral gay sensibility".

Homosexuality as a viable option has been repressed both in the lives of men and in their work, and it is easy to see how directors could be blind to their own subtexts. The taboo against male intimacy is taken more seriously onscreen than it is in real life. Director Robert Aldrich, whose film The Choirboys (1977) deals extensively with the fear of homosexuality in its graphic portrayal of homophobia among the Los Angeles police, recognizes a traditional male reluctance to deal with such things.

Some people contend that there is no such thing as a "gay sensibility", since the presence of such a thing would imply the existence of a "straight sensibility", which is something that unquestionably does not exist. Yet a gay sensibility can take on various forms and it is possible for it to be present, even when there is no indication of homosexuality, either overt or covert, in front of or behind the camera.

The need to conceal one's sexual orientation for such a significant portion of one's life is primarily responsible for the development of a gay sensibility. It is a ghetto sensibility that was developed out of the necessity to cultivate and employ a second sight, that would interpret discreetly what the world sees and what the actual reality may be.

It was gay sensibility that, for example, often enabled some lesbians and gay men, to see at very early ages, even before they knew the words for what they were, something on the screen that they knew related to their lives in some way. Often it was the simple recognition of difference. The sudden understanding that something was altered or not what it should be. Perhaps the role reversal of a Dietrich or a Garbo evoking a hidden truth about the nature of sexuality in general. Or it may have been the tone in James Dean's voice as he zipped up the jacket of the dead Sll Mineo in Rebel Without a Cause and muttered:

What was not omitted from The Mechanic and films like it was the sexual dynamic, which caused such critics as Vincent Canby of the New York Times to recognize that something more than simple male bonding was involved. People say that there can be no such thing as a "gay sensibility" because the existence of one would mean that there is a straight sensibility, and clearly there is not. But a gay sensibility can be many things; it can be present even when there is no sign of homosexuality, open or covert, before or behind the camera. Gay sensibility is largely a product of oppression, of the necessity to hide so well for so long. It is a ghetto sensibility, born of the need to develop and use a second sight that will translate silently what the world sees and what the actuality may be. It was gay sensibility that, for example, often enabled some lesbians and gay men to see at very early ages, even before they knew the words for what they were, something on the screen that they knew related to their lives in some way, without being able to put a finger on it. Often it was the simple recognition of difference, the sudden understanding that something was altered or not what it should be, perhaps the role reversal of a Dietrich or a Garbo evoking a hidden truth about the nature of sexuality in general. Or it may have been the tone in James Dean's voice as he zipped up the jacket of the dead Sal Mineo in Rebel Without a Cause and muttered, "Poor kid . .. he was always cold." It was the sense of longing that existed in such scenes, the unspoken, forbidden feelings that were always present, always denied. It said, this has something to do with your life, and it was a voice that could not be ignored, even though the pieces did not fall into place until years later.

Dean: "He's always cold..."

It was the sense of yearning that was there in these encounters. The unsaid forbidden desires that were always there, but were always repressed. Even if the parts did not fit together until years later, it was a voice that could not be ignored.

With no real homosexuals allowed on screen in the 40s and 50s, censors often began looking for these hidden messages. Sometimes they found them even when there were real things that were abundantly clear.

In the film Rope for instance, directed by Alfred Hitchcock in 1948, Farley Granger and John Dall play the role of two pretentious gay lovers who, on a whim, murder a former Prep School classmate. They do this because they believe they possess a superior intellect and are not morally responsible to a crass society. The censor's attention was drawn not to the exact relationship between the characters, but rather to the discourse between them.

Arthur Laurents recalls that when he finished his screenplay for "Rope", he left England for America. And while he was in America, the script was passed on by American censors.

"Rope came from an English play called 'Rope's End,' and while I was in New York, the producer Sydney Bernstein took a few passages from the play and put them back in the script. So when it came back from the Hayes Office, every one of those passages was circled, with the comment 'homosexual dialogue' written in the margin.

And do you know what they were?

It was simply that they were saying things like 'My dear boy' to each other, and the way that the English talked was known as 'fruity' over here."

With no "real" homosexuals allowed onscreen in the Forties and Fifties, censors often looked for hidden meanings. Sometimes they found them even when the real thing was abundantly clear. While on the lookout for overt references to stereotypical homosexuality, censors missed the ephemeral emotional commitments to the kind of male bonding that had characterized couples since Wings. In Alfred Hitchcock's Rope (1948), Farley Granger and John Dall are the pretentious homosexual lovers who on a whim murder a former prep school classmate, believing themselves of superior intellect and not morally responsible to a crass society. It was the inconsequential dialogue rather than the specific relationship that caught the censor's eye. Arthur Laurents recalls that when he finished his screenplay for Rope he left England for New York, and while he was in America, the script was passed on by American censors. "Rope came from an English play called Rope's End, " Laurents explains, "and while I was in New York, the producer Sidney Bernstein took a few passages from the play and put them back into the script. So when it came back from the Hays Office, every one of those passages was circled, with the comment "homosexual dialoque" written in the margin. And do you know what they were? It was simply that they were saying things like 'My dear boy' to each other, and the way the English talked was known as 'fruity over here."

It's actually a long-held myth within film circles that the reason Hitchcock filmed Rope to appear as one long unedited take was so that censors would be unable to force him to cut any perceived gay content without altering the artistic intent of the film.

There were also other more covert homosexual relationships in Hitchcock films, such as the one between Martin Landau and James Mason in North by Northwest, and more strikingly the one between Robert Walker and Farley Granger in Strangers On A Train. Nonetheless the filmmaker only seldom offered commentary on matters of this nature regarding his work. But Arthur Lawrence later said:

"We never discussed, Hitch and I, whether the characters in Rope were homosexuals, but I thought it was apparent. I guess he did, too, but it never came up until we got to casting.

We'd wanted Cary Grant for the teacher and Montgomery Clift for one of the boys, and they both turned it down for the same reason — their image. They felt they couldn't risk it.

Eventually John Dall and Farley Granger played the boys, and they were very aware of what they were doing."

He also stated that Robert Walker was the one who suggested playing Bruno Anthony as a gay character in the film Strangers On A Train.

There were other, more covert homosexual relationships in Hitchcock films, among them that of Martin Landau and James Mason in North by Northwest (1959) and, more striking, Robert Walker and Farley Granger in Strangers on a Train (1951). But the director seldom commented on such aspects of his work. "We never discussed, Hitch and I, whether the characters in Rope were homosexuals," Laurents says, "but I thought it was apparent."

I guess he did, too, but it never came up until we got to casting. We'd wanted Cary Grant for the teacher and Montgomery Clift for one of the boys, and they both turned it down for the same reason—their image. They felt they couldn't risk it. Eventually John Dall and Farley Granger played the boys, and they were very aware of what they were doing. Jimmy Stewart, however, who played the teacher, wasn't at all. And if you asked Hitchcock, he'd tell you it isn't there, knowing perfectly well that it is. He was interested in perverse sexuality of any kind, and he used it for dramatic tension. But being a strong Catholic, he probably thought it was wrong. The homosexuality between the two men, after all, in Strangers on a Train, isn't in the script, yet it's there. Farley Granger told me once that it was Robert Walker's idea to play Bruno Anthony as a homosexual.

The strangeness of their agreement was emphasized by the friction that it caused between his malignantly faye Bruno and Granger's golly gee tennis player Guy Haynes.

In compensation for the death of Bruno's despised father, Guy agreed to take the life of Bruno's undesirable wife and put an end to Guy's marriage. Bruno's homosexuality emerged in phrases that would be used progressively during the 50s to describe gays as aliens. Because of his icy demeanor, his dark imagination, and the elitist superiority that he exuded, he was an extension of the clever but lethal sissy archetype.

Walker's choice was particularly exciting in terms of the plot. The tension it created between his malignantly fey Bruno and Granger's golly gee tennis player, Guy Haines, heightened the bizarre nature of their pact. Bruno would kill Guy's unwanted wife, and in exchange Guy would murder Bruno's hated father. Bruno's homosexuality emerged in terms that would be used increasingly throughout the Fifties to define gays as aliens. His coldness, his perverse imagination and an edge of elitist superiority made him an extension of the sophisticated but deadly sissy played by Clifton Webb in Laura, Peter Lorre in The Maltese Falcon and Martin Landau in North by Northwest. A Bruno Anthony is what Hitchcock might [...]

Philip and Brandon, the lovers in Rope, were warped individuals who murdered out of a belief in their own moral and intellectual superiority. Which they believed placed them outside the law. By existing outside the culture, such gays were able to deny explicit homosexuality while at the same time reinforcing specific stereotypes.

This is how Oscar Wilde's The Picture Of Dorian Gray could reach the screen in 1945, shorn of its more bizarre sexual implications, while offering George Saunders as a symbol of sophisticated decadence. Such ghettoized characters pre-saged the gay-as-alien images of the 1950s, and had their roots in the same anti-intellectualism and mistrust of difference that had characterized the shaping of Hollywood's image of the "normal" American man.

Philip and Brandon, the lovers in Rope, were warped individuals who murdered out of a belief in their own moral and intellectual superiority, which they believed placed them outside the law. By existing outside the culture, such gays were able to deny explicit homosexuality while at the same time reinforcing specific stereotypes. This is how Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray could reach the screen in 1945, shorn of its more bizarre sexual implications while offering George Sanders ("I choose all of my friends for their good looks") as a symbol of sophisticated decadence. Such ghettoized characters presaged the gay-as-alien images of the 1950s and had their roots in the same anti-intellectualism and mistrust of difference that had characterized the shaping of Hollywood's image of the normal American man. In Frank Capra and Robert Riskin's original script for It Happened One Night (1934), for example, the character eventually played by [...]

The view of the homosexual as being alien to his own society was also present in the constant deletion of specific homosexuality from the screen adaptations of literary works. In 1945, Billy Wilder brought Charles Jackson's novel The Lost Weekend to the screen with Ray Milland as the alcoholic writer Don Burnham. In Jackson's novel, Burnham's alcoholism stems from a complex variety of reasons that include a father fixation and a false accusation of his having had a gay relationship with a college frat brother. In Wilder's version of The Lost Weekend, however, the motivation for Burnham's drinking becomes a simple case of writer's block.

The view of the homosexual as being alien to his own society was also present in the constant deletion of specific homosexuality from the screen adaptations of literary works in the Forties. In 1945, Billy Wilder brought Charles Jackson's novel The Lost Weekend to the screen with Ray Milland as the alcoholic writer Don Birnam. In Jackson's novel, Birnam's alcoholism stems from a complex variety of reasons that includes a father fixation and a false accusation of his having had a homosexual relationship with a college fraternity brother. (Other Jackson books had had gay themes; a subplot in The Fall of Valor involved a marine and a married man.) In Wilder's version of The Lost Weekend, however, the motivation for Birnam's drinking became a simple case of writer's block. Seemingly a victim of the same problems that would later beset Tom Lee in Tea and Sympathy, Jackson's Don Birnam is also "saved" by the love of a good woman. But in the film, Jane Wyman saves Ray Milland from his alcoholism, not from the cause of it. Paramount studio boss Buddy DeSylva stated the reason for the script changes: "If the drunk isn't an extremely attractive fellow who, apart from being a drunk, could be a hell of a nice guy, the audiences won't go for it."

The only frames of reference for the majority of gay people were these covert signals and hidden indicators of homosexuality in Hollywood movies. The majority of gay people learned about themselves mostly through movies that stated the rest of the world was straight. A documentary entitled Word Is Out which was released in 1977 demonstrated that the majority of gay people living in the United States had the misconception that they were the only ones like them in the entire world.

Several years later when the Supreme Court finally ruled that it wasn't obscene to portray homosexual content on screen, films that were more overtly gay helped pave the way for the legitimization of homosexual subject matter on screen. Nonetheless throughout the early and middle part of the 1950s, the invisibility of homosexuality was enforced with an almost fanatical paranoia.

The secret signals and hidden signs of homosexuality in Hollywood features were the only frames of reference for most gays, who learned about themselves chiefly from movies that said that the whole world was heterosexual. The Mariposa Film Group's documentary Word Is Out (1977) shows that, as a result of this silence, most gays across America believed that they were the only ones in the world. Years later, Fireworks would help to pave the way for the legitimization of homosexual subject matter onscreen when Supreme Court decisions involving the film's exhibition pronounced it not obscene in spite of its homosexual material. But in the early and middle 1950s, the invisibility of homosexuality was enforced with an almost fanatical paranoia.

The perversity of the outsider, the oddball, or the alien screen character, was very noticeable... in an era built around rigid conformity such as the 1950s. The equation between being different in any way... and being gay was easy to see.

Pop psychoanalysis was rampant in the Forties and Fifties, and gays were increasingly being defined in psychiatric jargon both onscreen and off. Suddenly people began talking about dominant mothers and weak, passive fathers. The perversity of the outsider, the oddball or the alien screen character was very noticeable in an era of rigid conformity such as the 1950s. The equation between being different in any way and being homosexual was easy to see.

In 1952's My Son, John, Dean Jagger and Helen Hayes played the distraught parents of a young man who is... well, not gay but a communist agent played by Robert Walker. When their suspicions about their son's activities are confirmed, it's an American Tragedy. Suddenly they see their son as shifty and unfamiliar, a thing with no respect for God or country. An unprincipled monster to whom they can no longer relate. The healthy family disappears. Walker's coldness, his superiority, and his open contempt for his parents and their way of life, conspire to create a perverse unnaturalness.

In Leo McCarey's My Son John (1952), Dean Jagger and Helen Hayes play the distraught parents of a young Communist agent (Robert Walker). When their suspicions about their son's activities are confirmed, it is an American tragedy. Suddenly they see their son as a shifty, unfamiliar "thing" with no respect for God or country, an unprincipled monster to whom it is impossible to relate as of old. The healthy family situation disappears. Walker's coldness, his superiority and his open contempt for his parents and their way of life conspire to create a perverse unnaturalness not unlike that of his sinister Bruno in Strangers on a Train. The parents' reaction on learning of their son's Communist activities is exactly the same as if they had discovered their child's homosexuality.

In a 1950 New York Times story, The Republican National committee chairman asserted that:

"Sexual perverts who have infiltrated our government in recent years are perhaps as dangerous as actual Communists."

By December of that year 4,954 suspected homosexuals had been removed from employment in the federal government. The Lavender Scare was gripping Washington, and with the help of a future president, would soon dig its claws deep into Hollywood as well.

In a 1950 New York Times story, Guy George Gabrielson, Republican National Committee chairman, asserted that "sexual perverts who have infiltrated our government in recent years are perhaps as dangerous as actual Communists." By December of that year, 4,954 suspected homosexuals had been removed from employment in the federal goverment.

Vito Russo's chapter goes on to talk about Lesbianism in the 50's: All About Eve, Caged, Children of Lonliness (which was actually made in 1939 but denied by the Code Office until 1953), and Glen or Glenda?. But James skips over these Lesbian and Trans movies and picks up with Rebel Without A Cause in Chapter 4 after his diversion about the Lavender Scare in Chapter 3.

[Patron credits start rolling as James talks in a small screen at the bottom.]

As we close out this episode I'd like to thank our patrons for making this series possible. YouTube isn't great when it comes to pushing LGBTQ content. In fact in most cases, they try their best to keep it hidden. So our amazing patrons are the reason that this channel keeps chugging along. If you'd like to become a patron and gain access to videos early, as well as patreon exclusive content like our podcast, movie watch-along parties, and the amazing community on our Discord, you can sign up at the link in the description for as little as a dollar a month. All right, now I'll let the credits roll, and I'll see you soon for Unrequited Episode Three Blacklisted.

[Patreon credits continue to roll over piano music.]